In life we make choices. These decisions, small or large, will narrate the way our lives unfold – determine its twists, turns, starts and stops.

Sometimes the choices we make will lead to a change. Positive change. Negative change. Great success or a colossal failure. Sometimes, what we thought were bad choices at first, turn out to be great ones. The truth is – most of our actions have unforeseeable and unexpected consequences on both our own lives and the lives of those around us.

At SHARE, we are everyday problem-solvers – we make decisions for brands.

The purpose of our decision-making is personal and emotive – it’s our mission to make their audience feel a certain way about a certain product. We explore and uncover actionable insights that inform world-class strategies, and in turn – these brands conquer.

This got me thinking – what if we could translate these skills, for use in our everyday lives. What if we could take advantage of data and strategy to make important life decisions.

Is it possible, using data, to become a completely informed, totally rational, logical and conscious decision maker? And will making optimal decisions with such precision improve our lives?

We’ll see.

American Churches

9.30AM, May 12th, 2018. New Hampshire Ave, Los Angeles, California.

We were 63 days into a USA-wide road trip. It was the morning after the night before. We were pressed into our rental vehicle, exhausted and battle-scarred. We were sharing elaborate travel ideas and carefully formulating decisions on where to head next. We had encountered a problem. We were totally strapped of cash – burnt out.

A few weeks previously, I had jumped 40 feet from a pedestrian bridge into the Colorado River, Austin Texas. It was a particularly bad decision considering our travel insurance provider ceased to exist.

We were passing a box of Cap’n Crunch between ourselves. Living out of a sedan. We had plans to stay in the country for a further 33 days. A meticulously planned route through 21 states, six months in the making. We were days behind schedule, $1000 out of budget – totally Lost.

It’s easy to lose sight of the reason why we actually wanted to achieve this country-wide feat. We needed a clearer, more accurate idea of where to go, and what to do next. Our next decision needed to be a good one – an optimal one.

In the next street, we could make out a tall, generally nice but slightly dated-looking building. As it turns out, it was the infamous Church of Scientology of Los Angeles.

I understand the scepticism that surrounds modern American religions. I am not religious and have no interest in buying into pseudo-scientific beliefs. However, I am interested in people and particularly, their behaviour. I am interested in society, politics, religion, and culture. I am interested in the influence belief systems can have on shaping our personalities, moral judgement, and way of life.

Scientologists actually believe that we can recall pain and emotion from past lives, to create a relaxed, receptive and co-operative state, and in turn, make better life decisions. Of course, I cannot credit or begin to legitimise past lives and reincarnation. However, I am intrigued by the idea that our decision making is self-constructed, and whether we can alter our thinking or not, the choices we make are largely down to our experience with life.

Life Strategy VS Work Strategy

I am 24. I owe the bank £2000. I owe my mother £4000. Since 18, I have been through five failed relationships. I have dropped out of university. I have lived in eight apartments over four years. I cannot pass my driving test. I have been a chef, a journalist and a recording artist. I have failed in all three departments. I like to think I score well above average in the realms of poor decision making.

In an adjacent world, I am a Creative Strategist at SHARE. Strategists have long been compared to master chess players. And in a networked world, strategy is no longer a punctuated series of moves. Industries have become boundless and permeable. Competitive threats and transformative opportunities can come from anywhere. Our job is to identify, explore and solve permeant business problems. And we do, every day.

We gather information with a shared goal in mind, and we’re great at it. We provide innovative uses of social listening, natural language processing and AI. We discover unrivaled and impactful insights and learnings, and we act on them.

There is a clear discrepancy in my life. I am a paid decision maker, but I cannot make effective personal choices. It seems, in our personal lives, strategic reasoning comes second.

At first, it may seem as if our work and life problems are incomparable – but day in, day out we employ strategy to solve problems our intuition cannot.

We find patterns in irregular environments. And just as we cannot rely on our intuition to make important brand decisions, we cannot always rely on intuitive-thinking in our own lives.

Brands and life alike, do not come to us with regular problems – the rules are always different. Defining the communications strategy for a global brand isn’t like driving a car – although we’re certain we’ve cracked it, we won’t know immediately if we’ve done something wrong. No brief is the same – we don’t get repeated opportunities to learn from our mistakes, so it’s always best that our answers are optimal.

What I’m trying to say is – it’s not every day, that certain choices present themselves. So it’s important we’re always fed all the right information to make the best possible decision.

In work, and in life.

After all, data is just another form of system 2-type thinking. But far more reliable.

In 1954 article ‘The Theory Of Decision Making’, Ward Edwards introduces ‘the economic man’. The economic man is a perfect decision maker, and possesses three major traits.

- He is completely informed.

- He is infinitely sensitive.

- He is rational.

However, Edwards soon discovers that the economic man is not a real man. Humans do not behave rationally, and there is a clear inconsistency in our decision making. The pendulum swings in a behaviouristic direction, and our choices are guided by our emotions.

At SHARE, however, we are completely informed. We understand all courses of action, and the outcome of those actions. Can the economic man exist in 2019?

We incite emotional reactions in advertising. We target audiences, providing them with small flashes of positive or negative feeling. We tag familiar things as good things, and show them to you over and over and again. Perhaps this is karma for taking advantage of everyone else’s buggy moral code…

In Descartes Error, Antonio Damasio describes a patient ‘Elliot’, a successful businessman who had a small brain lesion that affected his ability to feel emotion. In turn, he made better, logical decisions.

What if – instead of relying on a brain injury, we could utilise data and strategy to tailor optimal decisions. What if, in a sense we could see behind advertising and instead – the products sold themselves?

Life’s Crossroads

My mother has long compared the most difficult decision she ever made to a crossroads. In fact, she really was at a crossroads. Dave lived in Rugeley. Jon lived in Hednesford. My mother was somewhere along the A460, deciding who she wanted to spend the rest of her life with.

She was engaged to Dave. She loved Dave. She wasn’t sure if Dave loved her. She wasn’t sure about Dave.

She worked with Jon. She wasn’t sure if she loved Jon. She knew Jon loved her. She wasn’t sure about Jon.

What if the decision did not reside within my mother?

There are deep parallels between classic human problems and the canonical problems we encounter in advertising, particularly at SHARE. Unfortunately, in our own lives, we are fooled by intuition in a repeatable, predictable and consistent way. Rational thinking does not scale out in real life. Hence the now popular phrase, “Classic Will”.

But, what if we could go a step beyond rational thinking? What if we could optimise our thinking? What if we could make sense of the randomness and formulate decisions that are deterministic, exhausted and exact without much additional cognitive effort?

It’s easy to imagine a future where our human decision-making is wearable, automated, and requires no labour of thought. A world where we can compare our situation to millions of identical situations in real time, compare past outcomes and provide an optimal solution. Imagine access to unconscious, near-perfect decision making, flawless financial, career and relationship choices – a magic 8 ball that works. My father would of never quit his job at the call centre to sell bicycles. My mother would of never married Dave. We’re sure it would be owned by someone. And, we’re sure it would come at a price.

Born and Raised

Let’s step back a little. In order to better understand what is driving my poor decision making, it may be best to explore my moral domain. We all exhibit very different behaviour, and of course, moral domain varies by culture.

I grew up in South Wales. 98.3% of the population are white, working class. Our income, after housing costs, is less than 60% of median income. De-industrialisation and austerity has taken a heavy toll on working class communities. We are subject to low paid and unstable jobs, rising living costs and insufficient benefits. We are locked out from economic success. In areas like these, political decision making is driven by emotions of anger and frustration. Brexit is our greatest example.

Communities like ours saw Brexit, with all the uncertainties it would bring, as an alternative to the status quo. An affront to the UK’s middle class. A slap in the face. We couldn’t bare agreeing with those who we feel continually exploit, and ignore us. Instead, we felt distaste and disgust towards them, and allowed those emotions to guide our decisions.

However, for working-class communities all over the UK, the chaos of the NHS, Universal Credit, social cleansing and housing was our priority. And, we voted against it. We were morally dumbfounded. Our voting decision was driven by our emotional circuitry, and it certainly wasn’t optimal.

McCain lost the election in 2008 because many voters didn’t want truths and dignity, they wanted confirmation bias and a president that could help justify their hate. This is why McCain lost and in 2016, Trump won.

Who Am I?

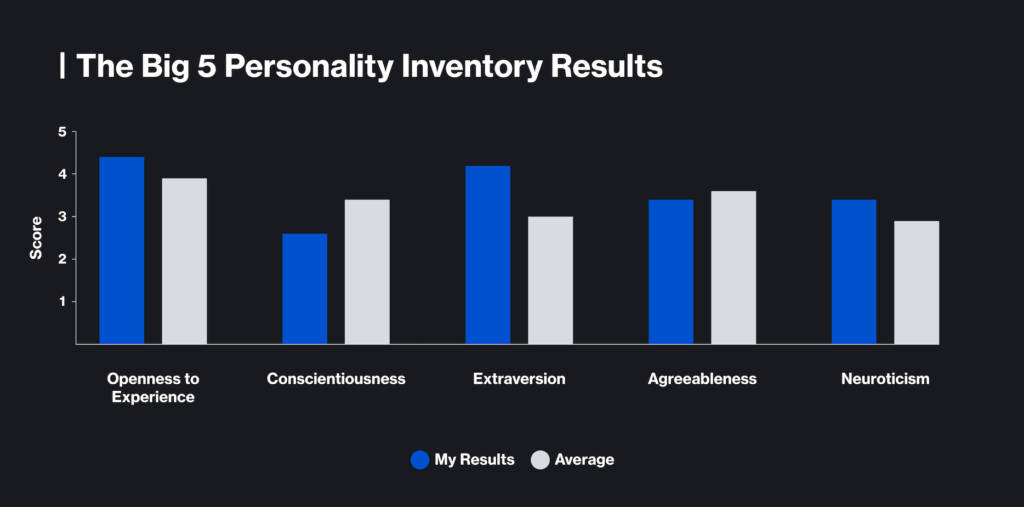

In order to better understand my character, I signed up to ‘Big 5 Personality Inventory’ created by Oliver John at the University of California, Berkeley. There are many scales out there to measure depression, anxiety, self-consciousness and other tendencies toward experiencing frequent negative emotions. However, the five-factor model has become the most important model in personality psychology. Originally developed by Paul Costa and Robert McCrae in the 1980s, the scale measures the five ‘master/meta traits’ of personality.

So, what kind of person am I? Can I employ data to optimise decisions that benefit me personally? As one of 93,354 visitors – my results (blue) are being compared to an average (grey).

I have a conscientiousness score that is far lower than average. Low scorers are easy going, not very well organised and sometimes rather careless.

I have an extraversion score that is well above average. High scorers are described as outgoing, active and prefer to be around people most of the time.

I also have a Neuroticism score that is above average. High scorers are sensitive, emotional and prone to experience feelings that are upsetting.

A combination of these behaviours, makes me the ideal candidate for decision-making optimisation: I actively make thoughtless personal decisions. These decisions determine not only my own fate, but those of others, and I tend to regret them afterward.

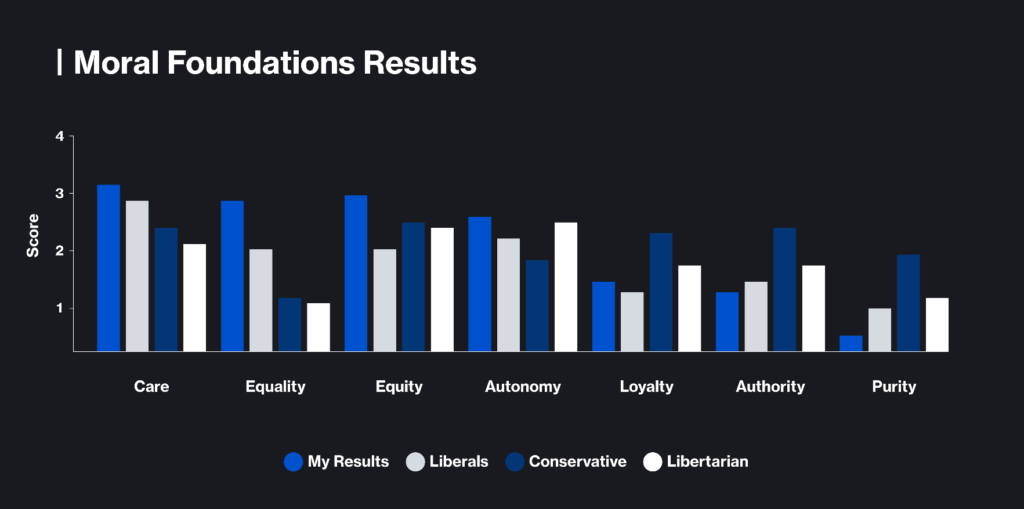

Am I The Good Guy Or The Bad Guy?

I also completed the ‘Moral Foundations Questionnaire’, developed by Jonathan Haidt, Sean Koleva, and Sean Stevens. The scale is a measure of my reliance on, and endorsement of six psychological foundations that can be found across different cultures. Simply put, the idea behind the scale is that human morality is the result of cultural processes that make human beings sensitive to different issues. A man in South Wales will possess different moral foundations to a man in Surrey. In turn, these emotions drive our actions. Question is – can we use data to bypass these signals?

Heads And Hearts

Truth is, we can either go with our head, or our heart. In an ideal world, we would make a rational decision and go with our head. It’s a sensible move that involves thinking and logical reasoning. But, what happens in the rare occasion our rational choice is a poor one? What if, just one time, our heart drives better decision making?

This is where data is so valuable. What if we didn’t have to go with our head, or our heart? What if we could leverage data and go with a million heads and a million hearts? What if, when faced with a permeant personal choice, we can compare the decisions made by millions faced with a similar choice, and just ride with it. No labour of love, hate or thought whatsoever. We’re simply emotionless and correct. We’re simply robots.

The Emotional Factory

Over a year ago I was working at a factory as a machine operator.

I was working with a man named Paul.

Paul was 42. Paul hated his job. Paul blamed this on immigration, overpopulation and lack of work.

As it happens, Paul is promoted and manages the packing area of the factory floor. His goal is to optimise the outgoing logistic flow of cakes. Paul still hates his job.

Robert, 21 works in the packing area. He is performing poorly and is fired by management. Aleks, a 24 year old Polish man is invited by management for a trial shift.

Aleks outperforms all workers in the packing area. Paul makes the final hiring decision. Paul’s goal is to make an optimal decision. Paul’s trusts his intuition and plans to tell Aleks no.

Paul’s emotions cannot be overcome. Paul judges Aleks on his race/nationality and ignores his impressive performance. Paul reasons with management, telling them that Aleks works too fast and is confusing orders. Of course, this is not the case. But when questioned, his poor decision-making is justified by other staff members with similar underlying beliefs – a support network that agrees with the dangerous, disorientated thinking of it’s team.

I spoke to Paul, and explained that hiring Aleks will improve his working conditions. I explained that Aleks should be judged on his capabilities, never by race.I told him that Aleks is a great worker, conscientious and will optimise the packing process. Aleks was hired.

Choices, big or small, are often driven by our emotions.

I will never read a book on philosophy. I attended a lecture in philosophy once and hated it. I will never watch Rick and Morty. A housemate of mine is a fan and never washes his dishes. I don’t listen to drum and bass music. I might like it, but my ex-girlfriend loved it. I can never make it to my friend’s gigs. I’m not busy, but I always wanted to be a musician myself.

The Social Intuitionist And The Social Reasoner

The social intuitionist model was published by Haidt in 2001.

Of course, intuitions come first and reasoning is usually produced after a judgement is made. However, as the discussion progresses, the reasons given by others can change our decision making.

What if we could eliminate our emotions? What if we could eliminate our intuition and judgement? What if our decisions were driven only by reasoning? And, what if that reasoning was drawn from the intuition and judgements of others, leveraged by data.

Until Next Time

In the coming weeks, I will apply the ‘social-reasoning model’ to my decision making. I will look at potentially thousands of others who have been presented with the same choice-triggering event as me, and use their experiences to apprise my reasoning and make my decision.

I will employ algorithmic-thinking to choices i would have otherwise made with ill-logic.

I will rely solely on data and strategy to inform decisions I would have otherwise made carelessly or emotionally – in a sense, optimising my life

Maybe life doesn’t have to be a rollercoaster.

And will I be a happier, economic man? Who knows.

Perhaps this is a small glimpse into a future where we live amongst robots, as robots. Or a future where only the super elite has access to world-class life-optimising tools…

Be sure to sign up to our mailing list so you don’t miss a thing – now that’s an optimal decision.

Who knows what might happen next? Data does.

Will Mills